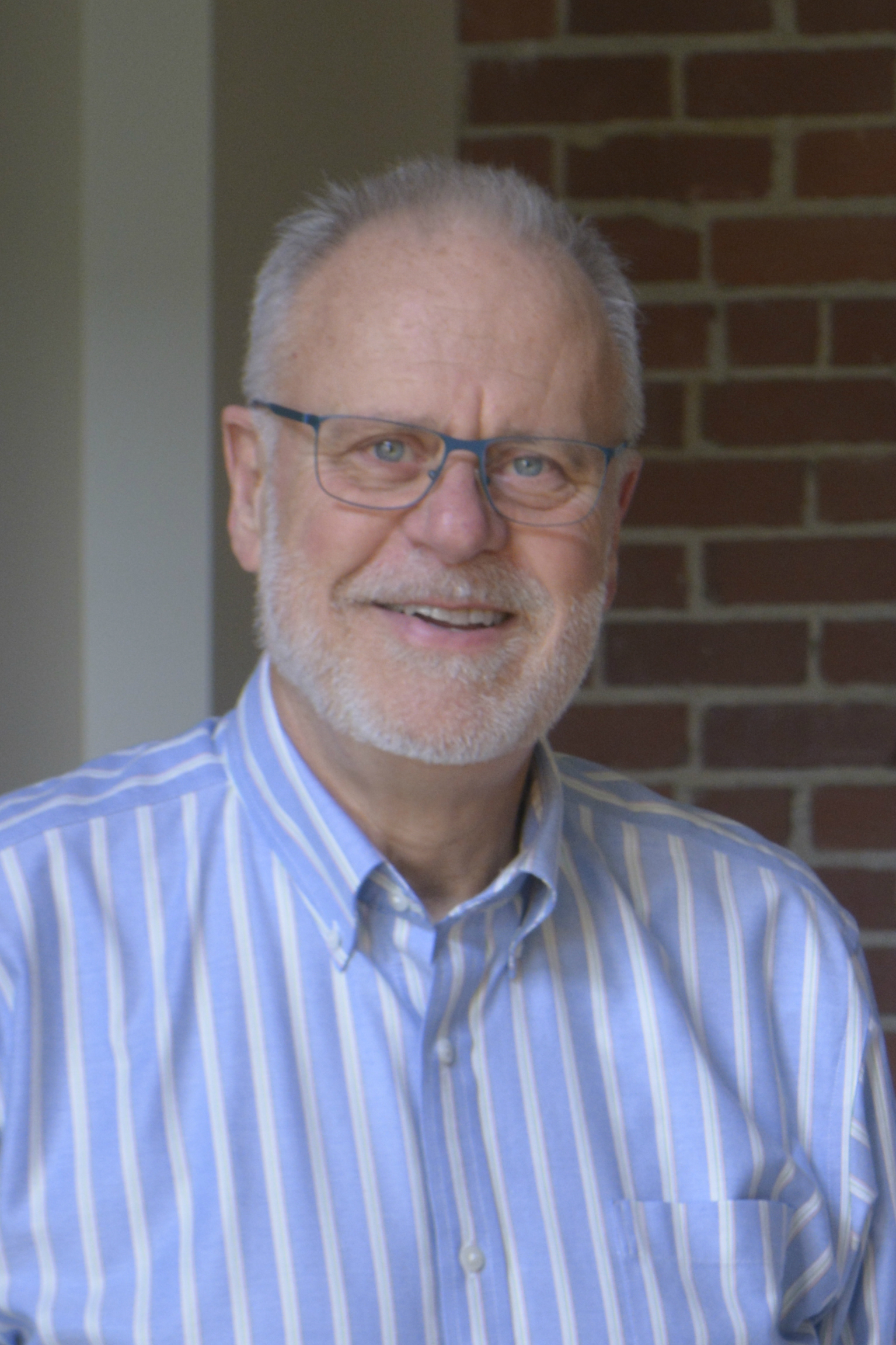

By Taylarr Lopez, Communications Specialist, NACCHO

NACCHO is pleased to recognize Patrick M. Libbey as the recipient of the 2016 Maurice “Mo” Mullet Lifetime of Service Award. This award honors current or former local health officials for noteworthy service to NACCHO that has reflected the commitment, vigor, and leadership exemplified by Mo’s distinguished career. Throughout Libbey’s more than 35 years in public health, he has demonstrated a steadfast commitment to advocating for and strengthening the work of local health departments (LHDs). He has also served NACCHO in a number of important capacities, amplifying the voice of local health departments at the national and federal levels.

Libbey served as NACCHO’s executive director from 2002 to 2008. During his tenure, NACCHO was increasingly recognized and engaged by a range of federal agencies and national organizations as a critical resource and partner, ensuring the perspective of local public health was considered in policy and program implementation and development. Libbey initiated the NACCHO Operational Definition, the organization’s effort to create a uniform, nationally shared definition and standards for a functional local health department. The Definition gained national recognition and acceptance and served as a key base for the emerging national voluntary public health accreditation effort. He served as NACCHO President in 2001–2002. He was a member of the NACCHO Board of Directors from 1992 to 2002; a member of the Executive Committee from 1994 to 2002; chair of the Education Committee; and chair of the County Forum.

Prior to joining NACCHO in 2002, Libbey was the director of the Thurston County Public Health and Social Services Department in Olympia, WA. Libbey is currently co-director of the Center for Sharing Public Health Services, a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation project helping public health officials and policymakers improve performance and efficiency through cross-jurisdictional sharing and regionalization.

NACCHO: Tell us about your career path in local public health.

Pat Libbey: I didn’t plan to go into public health initially. I previously worked in social services, behavioral health, mental health, developmental disabilities and substance abuse and managed those programs. As a result of a reorganization with the county I was working for, I was asked to take over the administration of the public health department in 1979. I found that work in public health at that time to be interesting and I was taken with the community development and the humanitarianism of the work. In my observation, public health was moving towards a community-based approach. I found myself increasingly engaged by public health. It was fulfilling and I felt I had something to contribute to it.

NACCHO: During your tenure as Executive Director for NACCHO, what do you consider your greatest achievement?

Libbey: It’s hard to isolate one thing but there are a few things that I’d like to highlight during my time at NACCHO. Firstly, when I arrived, there seemed to be some financial difficulties within the organization. Getting our financial house together and growing was a huge achievement for me and the organization. Additionally, under my direction, NACCHO successfully negotiated language that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention used that LHDs had to concur with on the state’s plans and proposed budgeted use of preparedness funds. That was a new approach and it was important specifically to the preparedness work but I think it also had implications in health departments in establishing their roles and identity with state health departments as equal partners.

Also, the development of the operational definition of a functional LHD was a huge accomplishment. We were successful in securing funds from a Robert Wood Johnson foundation and we put together a work team of local health, board of health and elected officials. One of the first major definitional works included (1) what is an LHD; (2) what is it expected to do; and (3) can we define that expectation in terms that have meaning to both the health officials and policymakers. In that operational definition, I think it became the real core underpinnings in the movement towards accreditation and the establishment of the Public Health Accreditation Board standards.

Lastly, partway through my tenure at NACCHO, we were able to pull together the first significant funding for health equity work and it really jump started NACCHO’s role as the thought leader. I believe NACCHO and the funding we were able to procure helped the governmental public health practice field to begin seeing issues of health equity and social justice as fundamental public health responsibilities.

NACCHO: You were a founding member of the Public Health Accreditation Board. In your opinion, what are the greatest challenges LHDs face in achieving accreditation? How can small LHDs with limited resources prepare for accreditation?

Libbey: There are a couple different linking challenges including the limited resources LHDs have to devote in terms of both time and money. LHDs may not have the necessary funds to document [everything that] is required in the accreditation process. An LHD must ask themselves if they have the resources to fill those gaps in seeking accreditation, which might be a dollar issue or another way of doing business. I think it’s compounded and difficult in what is still largely a categorical funding environment that doesn’t necessarily match up well with the accreditation domain. It’s both an art and a challenge to manage an LHD that is fee-supported or categorically driven with limited resources. The world of public health doesn’t stop while going through the accreditation process. There is ongoing work and emergent needs and that also is a challenge for LHDs trying to achieve accreditation.

Those small LHDs that are working towards accreditation, in some instances, require a new way of thinking about what public health is and can be in a community as opposed to being the administrator or provider of a collection of discreet services. Accreditation forces you to see yourself as a new whole in terms of your roles and responsibilities. I think in some ways when your core is smaller it’s harder to see your role in things that you’re not directly responsible for or managing. Smaller LHDs should question how they can partner with other sectors, organizations, and health departments in order to meet the measures and standards. Also, these LHDs can learn from other small departments that have completed the accreditation process.

NACCHO: In your nomination, your colleague mentioned you are politically astute but not partisan, evidence informed but not scientifically dogmatic, focused but not myopic, and so on. How important is it to you to remain balanced in the field of public health?

Libbey: I think balance is essential. Sometimes in public health we forget that there are multiple meanings to the word “public” in public health; there’s public process, public responsibility, public authority. These aren’t always vested in a health official. It’s always been my sense to get things done being “technically right” and sometimes the notion of being “technically right” isn’t enough to get things done. Sometimes if we present ourselves as knowing what’s right and rely solely on our science, we get some resistance. I think it’s more important to see where we can find common ground and find out where our interests and beliefs intersect. If it’s possible to work at that intersection, we can have a lot more success. I believe public health has shied away from the public policy and politics and that hasn’t served us well in the long run. At some point in finding that balance, there is a principle issue that you can’t move beyond in a compromising sense. If you start from the perspective of trying to find out the point of where both interests are served, public health can move forward more effectively.

NACCHO: What value do you find in attending the NACCHO Annual Conference?

Libbey: The NACCHO Annual Conference in particular is a learning opportunity where people get to learn from peers and the interaction is so important. It’s important for others to know what you do and vice versa. Also, you can learn from others’ experiences and find inspiration. The first NACCHO Annual Conference I attended gave me the chance to meet and talk with the local health official that was leading NACCHO’s initial work on community health assessment on APEX public health. He is a real leader. I learned from him and became his colleague and friend. The learning is both applied and visionary.

NACCHO: What does winning the Mo Mullet Award mean to you?

Libbey: On a personal level, I knew Mo. I worked with him and considered him a colleague and friend. I also feel he was a mentor to me and to others. To be honored in the same title as Mo has a huge personal meaning to me. I have a high regard for him and the work that he did, both for NACCHO and his counties in Ohio. As an acknowledgement of what I may have been able to do, in local public health in support of NACCHO, it’s a very strange combination of being both proud and humbled at the same time. I’ve gotten much from being part of NACCHO that to also then be honored by my peers as having made contributions at a level that warrant that award makes me proud.

NACCHO: What advice would you give to young professionals just starting their careers in local health departments?

Libbey: In local health, it’s not enough to have the public health background and training. There’s also the need to understand the dynamic of the community you’re working in and the role of being a “servant” in the public service sense. It’s important to know how to work for and with, and not lead or direct, the community you work with. These things are best learned through experience. Find the kinds of experiences that enable you to have time and opportunities for community engagement. Try to see how well-rounded [you can be] in terms of the range of public health roles that you can fulfill. At some point, there comes a time for young professionals to make a choice: (1) do you see yourself in a career in public health; or (2) is your career tied to the community that you’re working in? Although neither choice is right or wrong, it’s important to be conscious of both. Being aware of both those choices will shape what your professional career and development looks like. To start your career, it’s good to have a wide-ranging set of experiences at a community level.