By David Dyjack, DrPH, CIH, Associate Executive Director for Programs, NACCHO

Moshi is probably best known as a base camp for intrepid hikers wishing to scale Tanzania’s Mount Kilimanjaro’s 19,341-foot peak. I was seated in a small café in Moshi in August 1998, waiting my turn to ascend the mountain, when I learned from the BBC News about the bombings of the U.S. embassies in Dar es Salaam and Nairobi. As I reflected on the prior month, in which I had traveled throughout much of the horn of Africa, it was not just the victims of the senseless bombings who absorbed my thoughts and prayers. I was also deeply impressed by the conversations I had had with development and health professionals about the “weird” weather that year, which had damaged crops, infrastructure, and health centers. El Niño was reportedly to blame.

Moshi is probably best known as a base camp for intrepid hikers wishing to scale Tanzania’s Mount Kilimanjaro’s 19,341-foot peak. I was seated in a small café in Moshi in August 1998, waiting my turn to ascend the mountain, when I learned from the BBC News about the bombings of the U.S. embassies in Dar es Salaam and Nairobi. As I reflected on the prior month, in which I had traveled throughout much of the horn of Africa, it was not just the victims of the senseless bombings who absorbed my thoughts and prayers. I was also deeply impressed by the conversations I had had with development and health professionals about the “weird” weather that year, which had damaged crops, infrastructure, and health centers. El Niño was reportedly to blame.

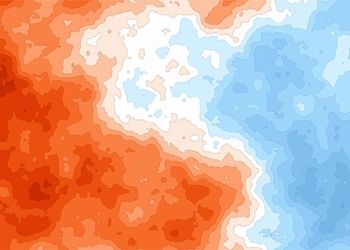

The year 1998 was indeed an interesting year for weather. Globally, heavy rains and flooding led to 23,000 deaths, loss of household assets and crops, and extensive damage to vital infrastructure in Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Somalia, and Kenya. The 1997–1998 El Niño also reportedly created conditions that gave rise to the massive forest fires in Indonesia. In recognition of the catastrophic conditions, the World Bank released emergency funds for transportation infrastructure, governmental health facilities, and water supply that had been badly damaged by excessive precipitation. Local weather had gone awry.

Fast forward to 2014. Headlines such as “Topsy-Turvy Weather to Persist” abound in news outlets. Data from ocean-observing satellites and other ocean sensors indicate that El Niño conditions appear to be developing in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. Conditions in May 2014 bear some similarities to those of May 1997, a year that brought one of the most potent El Niño events of the 20th century. What does all of this mean and what should public health professionals do about it?

If prevention is the hallmark of public health practice, then public health professionals can and should dispense with the academic debate related to extreme and unusual weather events and get down to business. Extreme weather events like El Niño are becoming more commonplace. Consider terms such as “polar vortex” and “derecho,” which appear to have migrated from the lexicon of a few learned individuals to the lingo of average citizens. Whatever the underlying reason, the current weather is disturbing the status quo.

When considering weather, people must differentiate weather from climate, which today is the center of attention. Weather describes the conditions of the atmosphere over a short period of time, and climate is how the atmosphere “behaves” over relatively long periods of time. Now, with that settled, what does all this mean to us in the greater public health network? My thoughts center on two major extreme weather issues—public health workforce training and energy and the urban environment

Public Health Workforce Training

Considerable attention has justifiably been paid recently to public health education, including the redesign of the entire enterprise from associate’s degrees through doctoral degrees. The majority of programs and schools in public health will likely embrace climate and weather change in their respective determinants of health academic offerings, either as a stand-alone course or embedded in a survey course in environmental health. While this is laudable, it is entirely appropriate to advance that conversation into other disciplines.

The topsy-turvy weather has immediate implications for the population at large. In illustration, the wet, cold winter of 2013–2014 and the sudden burst of warm weather have combined to create a pollen explosion. An article published last year in the journal CHEST declared that these conditions are a health threat no less consequential than cigarette smoking.[1] Reflect on that for a moment. Americans with asthma (25 million), allergies (50 million), diagnosed chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (15 million) and other respiratory conditions will die earlier or be in worse health because of pollen and other airborne contaminants.[2–4] In a play on words almost humorous, the term “pollen vortex” has entered the lexicon. This describes the condition of the potential overlapping of the two waves of pollen; ragweed pollen early in the year and grass pollen later in the year. The end result would be a super storm of air quality significance.

What are the implications for the public health workforce of the 21st century? As airborne pollen distribution fluctuates in composition and concentration as a function of changing weather, clinicians will need to know what to anticipate to be effective and efficient in their approach to treatment. Architects and land use planners may need to design communities and campuses with lower risk vegetation; engineers should factor the energy demands on public building ventilation systems equipped with higher efficiency filters; community health workers may need to become conversant in pollen science; and dieticians may be in higher demand to develop eating plans that do not exacerbate underlying conditions. I can also foresee a need for programmers to work with scientists to design mobile technology that provides real-time pollen exposure information for individual consumers. In summary, all professions associated with the public good will need to become more proficient at anticipating the risks and managing them in a coordinated fashion.

Energy and the Urban Environment

The United Nations predicts that, by 2050, 65 percent of people in the developing world and 86 percent of the developed country populations will live in urban areas. In the United States, the

2010 Census suggests a whopping 81 percent of us live in cities. The heat sinks associated with urban areas have been well observed and described. The critical nature of urban heat sink morbidity and mortality was made abundantly evident in 2003, when an unexpected heat wave was estimated to have resulted in 35,000 excess deaths across Western Europe, primarily among the elderly, who were not accustomed to elevated temperatures. As life expectancy continues to grow in the United States (of those who turned 65 last year, 20 percent will age to 90), public health professionals should consider the implications, particularly in areas where the electrical grid may be vulnerable.

Long-term care facilities for the aging population will be beyond the financial means for many and are not ideal for those who wish to age in place. The implications are staggering. Who or what sector is responsible for surveillance of the elderly during extreme weather events? Should this be a private or societal obligation? Perhaps the self-sufficiency of the Village to Village Movement offers some answers. These communities are committed to caring for all of their citizens.

While the aging population deserves special attention related to weather, the depressing fact is that about half of all American adults (117 million) have one or more chronic health conditions. One in four adults has two or more chronic diseases.[5] Extreme weather and the potential for interruptions in power and delivery of clinical services present special significance. Those who rely on dialyses or other energy-consuming treatments are at risk, particularly during a surge of need in highly populated urban areas. These at-risk individuals may compete for limited medical resources during extreme weather events, highlighting the value of medical-home preparedness and planning.

Public health professionals need to be forward thinking and invest in resilient, self-reliant communities because energy is the lifeblood for much of the U.S. infrastructure, including water systems, transportation, healthcare systems, and emergency operations. Texas and Louisiana personalized the lessons they learned from Hurricane Katrina and developed policies to ensure energy reliability for their critical infrastructure. I found in my own research that communities in southern California were amenable to partner with their local health department to prepare for all-hazards, including conditions anticipated during extended power outages.[6] Necessity is indeed the mother of invention.

Concluding Thoughts

Throughout the Unites States a natural experiment is underway. Extreme weather in the form of drought in California, snow in Atlanta, and flooding in Colorado illustrates the nation’s vulnerabilities. This is particularly true for the aging, increasingly urban, and chronic disease-afflicted populace. The U.S. workforce, visionaries, architects, engineers, clinicians, safety and health professionals, political leaders, and everyone with a stake in the design and function of society should become conversant in the weather conversation.

Albert Einstein once quipped that, if he had an hour to solve a problem, he would spend 55 minutes thinking about it and five minutes solving it. In 1998, the world I observed first-hand reflected the challenge of extreme weather on the functioning of society. Over the last 16 years, I have been thinking about the problem; it is now time for me and us to do our part in solving it. The glacier at the top of Kilimanjaro is almost gone, and with it the hopes and dreams of many who rely on the snow-melt for drinking and irrigation. Let us learn that lesson before it is too late. The evidence to support action is all around us.

About David Dyjack

David Dyjack is the Associate Executive Director for Programs at the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) where he oversees the organization’s grant portfolio and a staff of 75 health professionals in support of the nation’s 2800 local health departments. He can be contacted at [email protected].

This article was originally published in NACCHO Exchange. To read the entire issue, download the newsletter from NACCHO’s online bookstore. (Login required).

- Bernstein, A.S., and Rice, M.B. (2013). Lungs in a warming world. CHEST, 143(5):1,455–1,459.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). What is COPD? http://www.cdc.gov/copd/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Asthma: Fast stats. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/asthma.htm

- Asthma and Allergy Foundation. Allergy facts and figures. http://www.aafa.org/display.cfm?id=9&sub=30

- Ward, B.W., Schiller, J.S., & Goodman, R.A. (2014). Multiple chronic conditions among US adults: A 2012 update. Prev Chronic Dis,11:130389. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd11.130389

- Gamboa-Maldonado, T., Marshak, H.H., Sinclair, R., Montgomery, S., & Dyjack, D.T. (2012). Building capacity for community disaster preparedness: A call for collaboration between public environmental health, and emergency preparedness and response programs. Journal of Environmental Health, 75(2):24–28.