This guest post was written by Sarah Collier, MPH, Analytic Epidemiologist, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC’s new website, “Waterborne Disease in the United States,” is now live.

CDC epidemiologists have published the first comprehensive estimates of the burden of waterborne disease in the United States, showing that every year, diseases that spread through water cause 7.15 million illnesses and 6,630 deaths, and cost our healthcare system more than $3.3 billion. These data shed light on the waterborne disease challenges we face in the 21st century and what actions public health professionals can take to help mitigate waterborne disease threats.

Waterborne disease in the 21st century

Thanks to effective and consistent drinking water treatment, disinfection, and sanitation measures, gastrointestinal illness and death caused by drinking water pathogens (like cholera and typhoid) are much less common in the United States. However, waterborne pathogens still sicken and kill people.

We are learning that waterborne diseases are responsible for many different types of illnesses—including respiratory illnesses, neurological illnesses, skin problems, gastrointestinal illnesses, and bloodstream infections—which lead to 601,000 emergency department visits and 118,000 hospitalizations annually. People are infected by waterborne pathogens not just when they drink water. The pathogens causing these diseases can also enter people’s bodies when they breathe in contaminated water droplets or when water gets in their ears or nose.

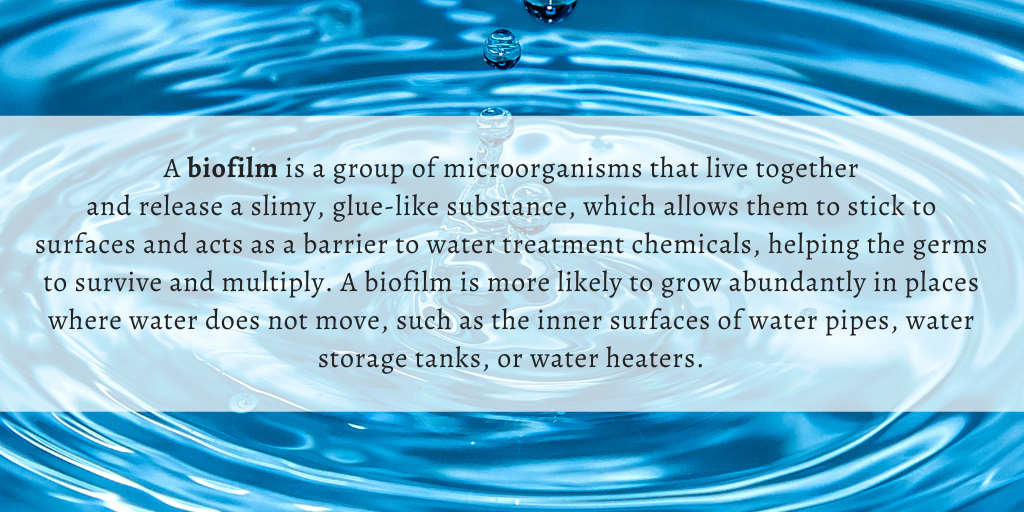

Common diseases like otitis externa (swimmer’s ear), norovirus infection, giardiasis, and cryptosporidiosis account for 95% of all waterborne illnesses. However, 94% of all deaths are caused by diseases from pathogens that live in biofilm (see box below)—nontuberculous mycobacterial infection [NTM], Legionnaires’ disease, Pseudomonas pneumonia, and Pseudomonas septicemia.

The shifting nature of waterborne disease

How did biofilm-related diseases become such a significant driver of the waterborne disease burden in the United States? To understand what caused this change in the types of waterborne disease threats we are facing, we must look at the ways in which our water use has evolved over the last few decades and the state of our water system infrastructure.

Our need to use water on a larger scale and in new ways grew along with our population. As cities grew, high rises, hospitals, water parks, cooling towers, and other large structures were built. These required complex water systems, many of which were added to existing piping systems that were designed in the early 1900s. There are now 6 million miles of indoor plumbing in the United States. It can be difficult to maintain adequate disinfection levels and consistent hot water temperatures in these millions of miles of plumbing. There can also be stagnant areas within the pipes where water sits for long periods of time. This creates the perfect environment for biofilm-related pathogens to grow (e.g. NTM, Pseudomonas, and Legionella) in biofilms. On top of this, our deteriorating water infrastructure is overwhelmed by the millions of pipes that are decades past their lifespan. These pipes create continual maintenance issues that can develop into emergency situations (e.g., a water main break), during which pathogens may contaminate water in the system.

Where do we go from here?

The health of our nation is closely tied to the safety of our water supply and water systems. The future of waterborne disease prevention will rely on maintaining the public health progress made over the last century while identifying and implementing solutions to protect people from current and future threats. To do this, we need a comprehensive approach that brings together policy makers, industry partners, building managers, public health, and other stakeholders.

As public health professionals, we can work to better understand how to best control and prevent waterborne pathogens through increased surveillance, research, analysis, and the subsequent creation of best practices for waterborne disease prevention. We also can engage in and support others’ efforts to develop and disseminate prevention messages. At CDC, we are in the initial stages of our follow-up analysis of the disease burden data, which will create more detailed estimates of how much waterborne disease can be attributed to drinking water, recreational water, and other types of water.

Although waterborne disease prevention presents ongoing challenges for the public health community, we believe there are many opportunities to address these challenges with science-based interventions. CDC looks forward to supporting and collaborating with local, state, tribal, and territorial public health partners to protect all Americans from waterborne disease.