In 1897, British doctor Sir Ronald Ross made the discovery that female mosquitoes transmit malaria between humans. This discovery allowed for an understanding of the malaria life cycle in mosquitoes, which was essential in building control efforts. Unfortunately, malaria continued to account for 2 to 5 percent of all deaths through the 20th century1. Although advancements in research and medicine have improved prevention and treatment of malaria, today nearly half of the world’s population is still at risk, thanks to a warming climate.

In addition to malaria, other diseases that are spread by mosquitos between humans include:

- West Nile Virus (958 cases reported in the U.S. in 2019)

- Eastern equine encephalitis virus (38 cases reported in the U.S. in 2019)

- Chikungunya Virus (171 cases reported in the U.S. in 2019)

- Dengue (1,203 cases reported in the U.S. in 2019)

- Zika Virus (while there were 0 cases reported in the U.S. in 2019, outbreaks in 2015 and 2016 resulted in over 5,230 cases reported in the U.S.)

- Yellow Fever

Risk of certain mosquito-borne diseases, as well as other vector-borne diseases, are changing along with our climate. Hurricanes, which are increasing in extremity and frequency, result in standing pools of water which serve as breeding grounds for mosquitoes. A prolonged rainy season could also increase the risk for the introduction and establishment of new vectors. Increases in temperatures across the country allow for the expansions of ticks as well as mosquitoes into areas where they previously did not exist. West Nile Virus and Lyme Disease provide great examples of how climate change has propagated vector-borne diseases in the U.S.

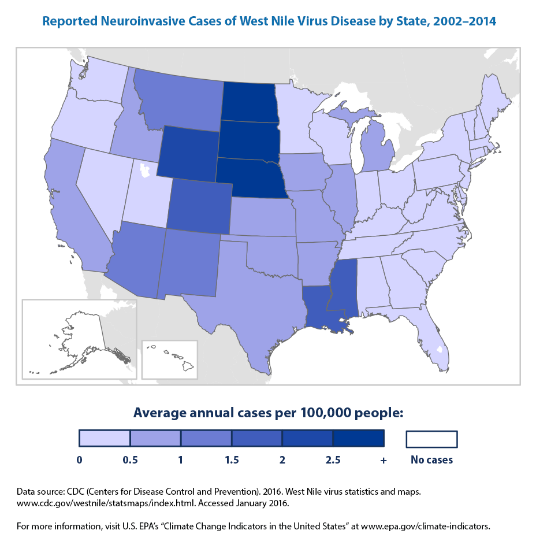

- West Nile Virus was first detected in the United States in New York City, 1999. That summer had recorded the warmest July ever in Central Park in Manhattan, which increased the abundance of urban Culex mosquitoes2. Since then, is now the most common cause of mosquito-borne disease in the U.S. In 2018, over half of reported cases were neuroinvasive, affecting the brain or causing neurologic dysfunction.

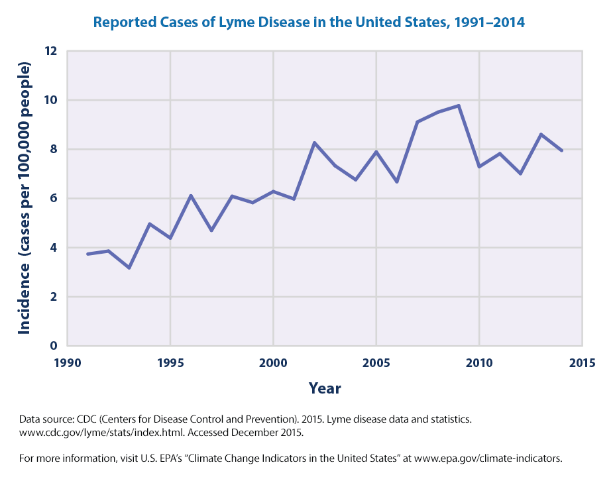

- Lyme Disease is the most common vector-borne disease in the U.S. The life cycle of ticks is strongly influenced by temperature, permitting climate change to increase the range of suitable tick habitats. Northern states (Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont) have experienced the largest increase in reported cases since 1991. Although most individuals diagnosed with early, acute Lyme are properly treated and make a full recovery, chronic Lyme patients face several challenges when accessing treatment. A 2018 report from the Tick-Borne Disease Working Group noted that 49.5% of chronic Lyme patients surveyed reported travelling 51 miles or more to see a treating doctor, and half of respondents saw at least seven physicians before their diagnosis of chronic Lyme was made. This rising disease fueled by our changing climate is burdensome on the healthcare system, but especially the individuals directly affected.

Vector control programs at local health departments (LHDs) play an important role in protecting public health. In addition to vector surveillance, control, identification, and research, these programs are also responsible for public outreach and education. Unfortunately, only 55% of LHDs provide vector control services, with these programs being less common in rural areas and areas with small populations (< 50,000 people). At these LHDs, many of which are still dealing with the budget and staffing cuts from the 2008 recession, the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted routine operations, reassigning limited staff to outbreak response and reallocating PPE which are used for chemical control applications.

NACCHO supports LHDs in protecting their communities from the bacterial and viral diseases transmitted by mosquitoes, ticks, rodents, and other emerging vectors. Through development of new tools and resources, research, policy statements, Stories from the Field, and more, NACCHO helps local health departments and local programs increase their capacity to address existing and emerging issues related to vector control and integrated pest management.

What can LHDs do?

- Consider becoming a Climate for Health Ambassador. These Ambassadors are health professionals who are trained to advocate for solutions to climate impacts. NACCHO recently hosted a training to offer this training to local health departments, including members from vector control programs.

- Apply for NACCHO’s Vector Control Collaborative , which has created a network of local vector control organizations that share resources, experiences, and lessons learned with other local vector control programs. Since launching the VCC in 2018, NACCHO has awarded over $172,000 to 28 programs across eleven states. Visit NACCHO’s vector control webpage for information on upcoming cohorts, or email [email protected].

- Spread the word on NACCHO’s 2019 Profile findings on the impact of vector control programs, and NACCHO’s special report on COVID-19 impact on local vector control programs.

- Check out NACCHO’s blog on foundational training resources on Vector Control to sign up for several online and in-person courses.

- Contribute a guest blog to NACCHO featuring your LHD story at the intersection of climate change and vector control. Email Anupama Varma at [email protected] if you are interested.

References:

[1] Carter, R & Mendis, KN. (2002). Evolutionary and historical aspects of the burden of malaria. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 15(4), 564 – 594.

[2] Brault, A.C. and Reisen, W.K. (2013). Environmental perturbations that influence arboviral host range. In Viral Infections and Global Change, S.K. Singh (Ed.). doi:10.1002/9781118297469.ch4