Authors: Jack Herrmann, MSEd., NCC, LMHC, Senior Advisor & Chief, Public Health Programs, NACCHO; Alyson Jordan, MPA, Communications Specialist, Public Health Preparedness, NACCHO; and Justin Snair, Senior Program Analyst, Public Health Preparedness, NACCHO

Twelve years ago today, the United States experienced the worst terrorist attack on our soil, which since has shaped the ebb and flow of public health preparedness policy and funding. Catastrophic events such as 9/11, Hurricane Katrina, and the H1N1 influenza outbreak led to an infusion of federal funding to state and local governments that soon dried up after each response ended. Between 1985 and 2004, on average, the government spent annually 15 times as much on disaster relief as on preparedness.[1] Because funding has been mainly reactionary, many local health departments increase their programs and workforce to respond to events, and then as federal funding gradually decreases, they are forced to cut their staff and programming. This response-focused funding cycle creates inefficiencies and challenges in all levels of government, and costs more than if the investment had been made in preparedness activities upfront, leaving communities scrambling to respond to the next event.[2]

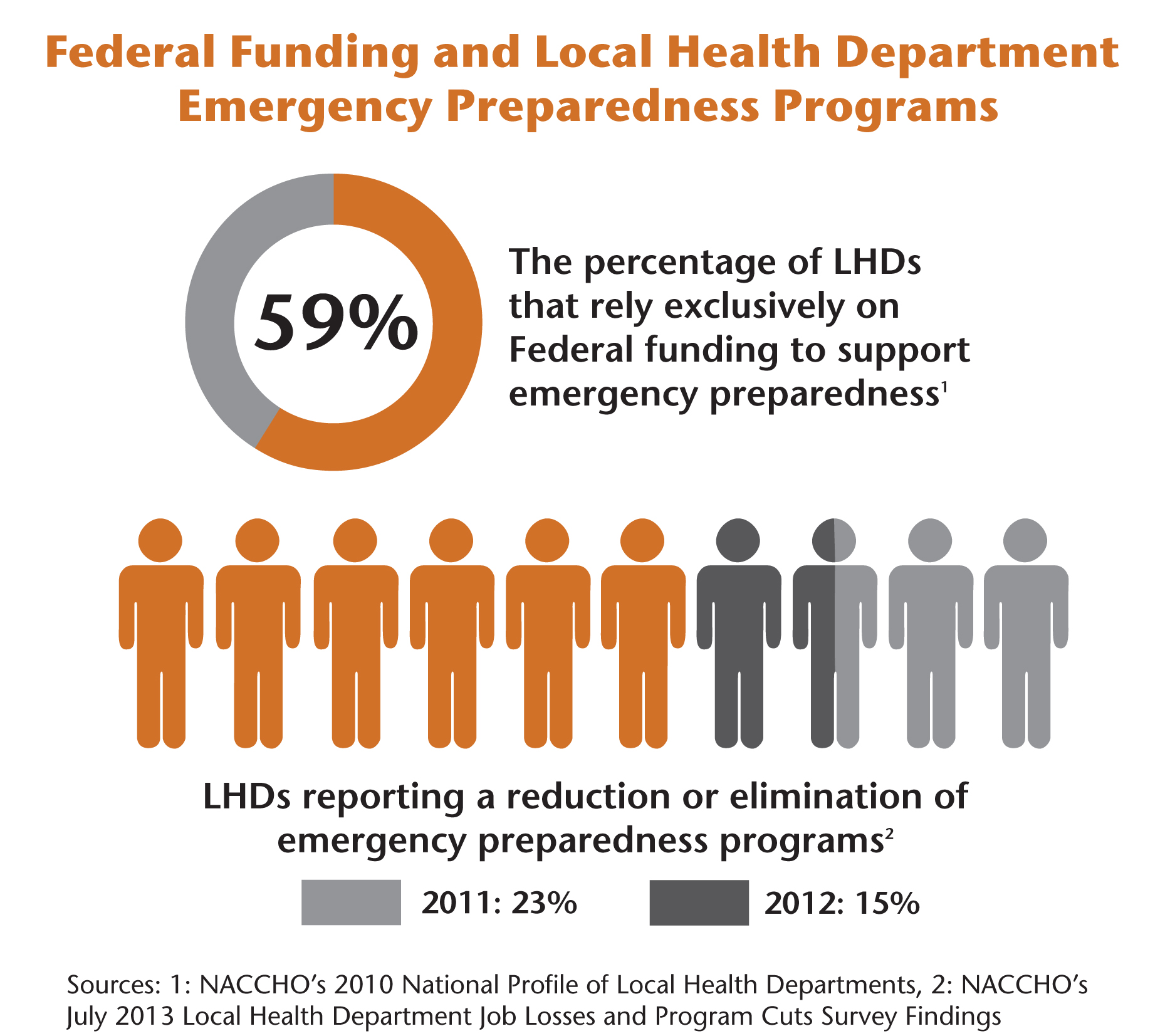

With public health preparedness funding and jobs shrinking, communities are vulnerable to emerging threats. From FY2012 to FY2013, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services cut $35 million from Public Health Emergency Preparedness funding[3] and $20 million from the Hospital Preparedness Program.[4] Further cuts are proposed for FY2014, which will directly affect local health departments. As indicated in NACCHO’s 2010 National Profile of Local Health Departments, 59 percent of local health departments rely solely on federal funding for public health preparedness. Today, NACCHO released the latest report in a series revealing the impact of budget cuts at the local level. This report shows that 23 percent of local health departments reduced or eliminated at least one emergency preparedness program in 2011, and the trend continued in 2012 with a 15 percent reduction.

With public health preparedness funding and jobs shrinking, communities are vulnerable to emerging threats. From FY2012 to FY2013, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services cut $35 million from Public Health Emergency Preparedness funding[3] and $20 million from the Hospital Preparedness Program.[4] Further cuts are proposed for FY2014, which will directly affect local health departments. As indicated in NACCHO’s 2010 National Profile of Local Health Departments, 59 percent of local health departments rely solely on federal funding for public health preparedness. Today, NACCHO released the latest report in a series revealing the impact of budget cuts at the local level. This report shows that 23 percent of local health departments reduced or eliminated at least one emergency preparedness program in 2011, and the trend continued in 2012 with a 15 percent reduction.

Although local health departments routinely struggle with budget cuts, in the past they have received increased federal funding in response to catastrophic events. During the H1N1 influenza outbreak in 2009, Congress appropriated over $1.4 billion through the Public Health Emergency Response grants to respond to the pandemic.[5] While all 50 states and eight territories received funding through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, H1N1 after-action reports highlighted administrative hurdles at multiple levels. Officials cited problems accepting, allocating, and spending funds, as well as a lack of alignment with their grant cycle and/or state fiscal year.[6] Despite these challenges, data showed that the American public supports response-based funding more than preparedness funding, with a significant relationship demonstrated between relief spending and voter decisions.[7] This incentivizes lawmakers to continue the reactionary funding practice, as increases in relief spending have been shown to gain additional votes.[8]

To ensure consistent and efficient preparedness activities and response capacity, reactionary funding cycles should be supplemented with more routine preparedness funding. While this pattern may not change for some time, local health departments should take steps to avoid conforming to this reactionary model. Local health departments have a responsibility to prepare their communities for emergencies with or without assistance at the federal level. Pursuing a “whole community approach” to financing preparedness could engage stakeholders who are not typically involved with preparedness planning. Health officials could work with private local businesses, nonprofit organizations, and other partners to encourage investments in preparedness. They also could investigate alternative methods to finance preparedness planning, such as through innovative bonding, private investments, and new sources of revenue. These methods might include public health preparedness surcharges on business operation permits or workforce surge fees in communities with a daytime influx of workers from out of the jurisdiction.

Communities could also use alternative resources to prepare for and respond to emergencies. Although local health departments have lost expertise through personnel cuts, they could engage their local Medical Reserve Corps (MRC) units to augment the local public health workforce during times of surge or for routine public health activities. During Hurricane Sandy, nearly 100 local health departments benefited from the work of MRC volunteers who helped with preparedness outreach before the storm, sheltering, and recovery activities. Local health departments could also put administrative preparedness policies in place to expedite administrative procedures during an emergency; the 2013 NACCHO report “Administrative Preparedness Authorities: Suggested Steps for Health Departments” outlines helpful strategies.

In the coming weeks during National Preparedness Month, illustrate the success of your preparedness planning by sharing your story of how preparedness has demonstrated a return on investment in your community. Help break the cycle of reactionary funding. Local health departments prepare communities for disasters, respond if emergencies occur, and lend support throughout the recovery process. Educate your policymakers and the public about the importance of preparedness programming and investments in alternative resources.

For more information on today’s survey findings, view “NACCHO’s July 2013 Local Health Department Job Losses and Program Cuts Survey Findings” report and press release.

[1] Surowiecki, J. (2012, December 3). Disaster economics. Retrieved from http://www.newyorker.com/talk/financial/2012/12/03/121203ta_talk_surowiecki

[2] Healy, A., & Malhotra, N. (2009). Myopic voters and natural disaster policy. American Political Science Review, 103(3), 387-406. Retrieved from http://myweb.lmu.edu/ahealy/papers/healy_malhotra_2009.pdf

[6] National Association of County and City Health Officials. (2013). Report: Administrative preparedness authorities: Suggested steps for health departments. Download at http://bit.ly/18SqRPR

[7] Healy, A., & Malhotra, N. (2009). Myopic voters and natural disaster policy. American Political Science Review, 103(3), 387-406. Retrieved from http://myweb.lmu.edu/ahealy/papers/healy_malhotra_2009.pdf

[8] Ibid.